The Paediatric Surgery Unit of the Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM), sees the culmination of a three-year effort when their international collaborative research found that the survival of a baby born with a birth defect is geographically dependent.

Subscribe to our Telegram channel to get a daily dose of business and lifestyle news from NHA – News Hub Asia!

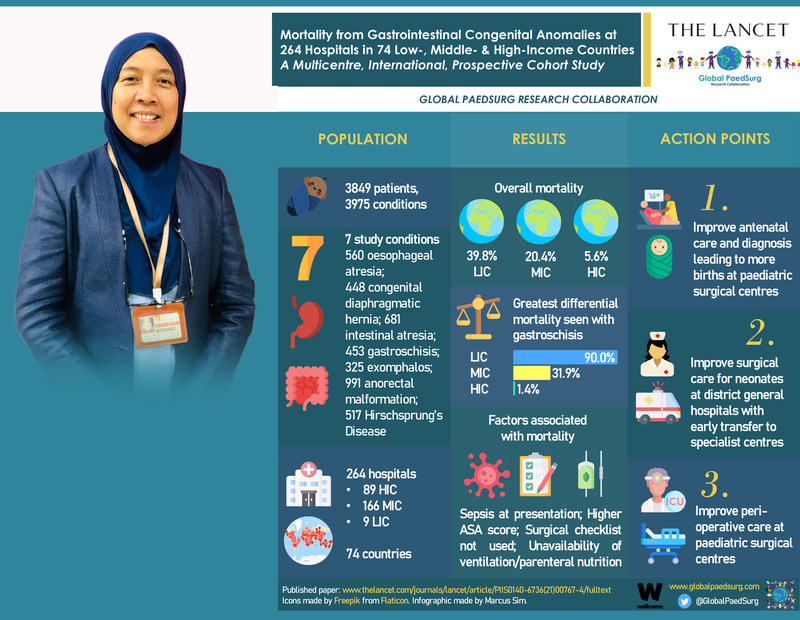

The study, which was published in The Lancet, examined the risk of mortality for nearly 4000 babies born with birth defects – otherwise known as a congenital anomaly – in 264 hospitals around the world.

The research was spearheaded by Senior Consultant Paediatric Surgeon at the Faculty of Medicine UKM Professor Dr. Dayang Anita Abdul Aziz as institutional, country and regional lead for ASEAN. It saw the collaboration of 1387 researchers from 74 countries.

Professor Dr. Dayang Anita stated that local medical centres also contributed to the study, particularly in terms of ethical clearance and data collection.

She explained that improving patients’ care can have a significant impact on their lives.

“Some of the congenital anomalies like gastroschisis can look really unpleasant, but with immediate and proper attention, the condition is treatable,” she said.

In low-income countries, babies born with intestinal birth defects have a two-in-five chance of dying, compared to one in five in a middle-income country and one in twenty in a high-income country, according to the study.

Gastroschisis – a birth defect where the baby is born with their intestines protruding through a hole by the umbilicus. There is the greatest difference in mortality with 90 per cent of babies dying in low-income countries compared with one per cent in high-income countries. In high-income countries, most of these babies will be able to live a full life without disability.

Principal Investigator Dr. Naomi Wright, who has devoted the last four years to studying these disparities in outcomes, said that geography should not determine the outcomes for babies with correctable surgical conditions.

She said: “The Sustainable Development Goal – to end preventable deaths in newborns and children under five years old by 2030 – is unachievable without urgent action to improve surgical care for babies in low and middle-income countries.”

The team of researchers stressed the need for a focus on improving surgical care for newborns in low and middle-income countries globally.

Over the last 25 years, while there has been great success in reducing deaths in children under five years old by preventing and treating infectious diseases, there has been little focus on improving surgical care for babies and children and indeed the proportion of deaths related to surgical diseases continues to rise.

Birth defects involving the intestinal tract have a particularly high mortality rate in low and middle-income countries, as many are not compatible with life without emergency surgical care after birth.

In high-income countries, most women receive an antenatal ultrasound scan to assess for birth defects. If identified, this enables the woman to give birth in a hospital with children’s surgical care so the baby can receive help as soon as it is born. In low and middle-income countries, babies with these conditions often arrive late to the children’s surgical centre in a poor clinical condition.

Studies have shown that babies who are presented to the children’s surgical centre are already septic with the infection and have a higher chance of dying.

It also highlights the importance of perioperative care, which is the care received on either side of the corrective operation or procedure at the children’s surgical centre.

The team of researchers found that improving survival from these conditions in low and middle-income countries involves three key elements – improving antenatal diagnosis and delivery at a hospital with children’s surgical care; improving surgical care for babies born in district hospitals, with safe and quick transfer to the children’s surgical centre; as well as improved perioperative care for babies at the children’s surgical centre.

“We can make a difference in these newborns if we equip the hospitals with a complete team of experts, namely neonatologists and paediatricians, paediatric surgeons, paediatric anaesthetists, availability of intensive unit care, antibiotics and parenteral nutrition,” Professor Dr. Dayang Anita added.

The researchers urge that alongside local initiatives, surgical care for newborns and children needs to be integrated into national and international child health policy and should no longer be neglected within global child health.

SOURCE Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (press release)